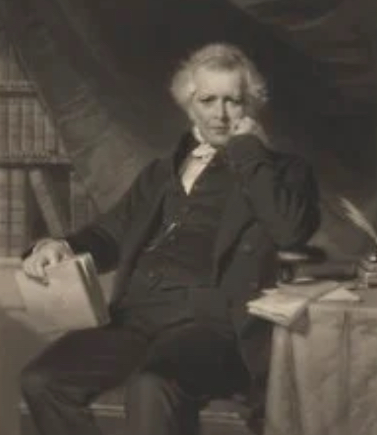

Henry Venn (1796-1873) was both an extraordinary Christian leader of his day and a hugely important figure in cross-cultural mission thinking. He was a man of many parts, with a significant impact on the British political scene of his day. He was a campaigner, in the tradition of the Clapham Sect, who fought to ensure the total eradication of the Atlantic slave trade. In his later years, his position as an evangelical in the Church of England was recognised by his being placed on two royal commissions.

Venn was an Anglican clergyman who is recognised as one of the foremost Protestant missions strategists of the nineteenth century. Two men of whom I have written over the last few weeks, John Nevius and Roland Allen (see below), both based some of their work on Henry Venn’s thinking. Venn served as honorary secretary of the Church Missionary Society from 1841 to 1873. “He expounded the basic principles of indigenous Christian missions: these were much later made widespread by the Lausanne Congress of 1974.”

Venn was born in Clapham, London, into a leading evangelical Anglican family. His grandfather, Henry Venn (1725-1797), was an outstanding pastor-evangelist identified with the Evangelical Revival. His father, John Venn (1759-1813), was pastor to William Wilberforce and the Clapham Sect. His father also presided over the formation of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in 1799. CMS included men like William Wilberforce and John Newton. Together, they worked to abolish the slave trade “and they launched out onto dangerous seas to share Jesus with the world.”

Venn is best remembered, however, as a mission theorist. He worked largely independently of his American contemporary Rufus Anderson (1797-1880) who worked with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Yet they both used the term “indigenous church” in the mid-nineteenth century at the centre of their mission strategies.

Venn saw that the missionary movement operated without a special theoretical or theological framework, thus he frequently mentioned the need to identify and codify missionary principles. Toward the end of his life, he spoke of the “science of missions”. This reflected his personal commitment to search for clear principles that would replace the weaknesses in the newly created missionary-founded, missionary-led churches in nations overseas. He argued that the new churches had to feel self-worth.

This required three elements being put into place:

1. Leadership (self-governing). A church must be led by persons drawn from its own membership. So long as a group of people must look to an outsider to furnish leadership, they will feel less than fully responsible.

2. Finance (self-supporting). The local believers must support the life of the church financially. Without that, their membership will lack integrity.

3. Evangelism (self-propagating). The local church must be those who evangelise and thus bring church growth.

Thus Venn birthed and promoted the concept of the Three-Self Church. This was the original and genuine use of a term which has been somewhat hijacked more recently by the Chinese Communist authorities.

Venn likened the relationship between church and mission to that of a new building and the scaffolding around it. From this, he derived the oft-quoted phrase, “the euthanasia of a mission.” That meant that missionaries were to be considered temporary workers and not permanent ones. They should be working themselves out of a job by creating the local indigenous church. This concept “presupposed that when a vigorously mission-minded church had developed, then a formal mission structure was an abnormality to be removed as early as expedient.” The mission calling was to be engaged in continuous advance into the “regions beyond”. When a local church was birthed, it should send out its own missionaries to other unreached areas. For example. Samuel Adjai Crowther was sent from Sierra Leone to Yorubaland in 1845 and later to the Niger Delta.

The integrity of the young church was central to his system of thought. In the last decade of his work with CMS, he was particularly intrigued with cases of “spontaneous” expansion, raising the important balance between the role of the missionary and the work of the Holy Spirit in mission.

Remarkably, Venn never visited any of the missions overseas. “He was an avid and astute reader of missionary reports. He early learned to make allowance for lack of perspective in missionary accounts and mistrusted the ‘romance of missions’. He maintained a wide circle of friends among Africans and Asians and entertained them in his home when they came to London. These contacts had a definite influence on the development of Venn’s policies.”

Henry Venn died on January 13, 1873 and was buried, according to his request, in a plain wooden coffin. The missionary theme of the hymns sung on that occasion pointed to his lifelong commitment to world mission. We owe much today in cross-cultural mission thinking to this man who never went!